UPDATE:

Doveson2008 kindly returned to the original slide, rescanned it and provided a great deal of additional information besides. Armed with that, Matthew and I have been able to pin down the exact time, date and occasion on which this photograph was taken.

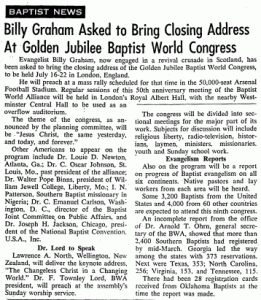

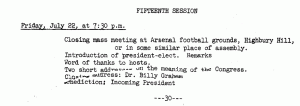

It’s c. 6.30pm on Friday, 22nd July 1955. The Baptist World Alliance have been holding their golden jubilee conference at the Albert Hall since the previous Saturday, and what you see here is Billy Graham’s rally for delegates at Highbury. It was due to get underway at 7.30pm.

The original slide has “BWA Rally” written on the frame, and the frame turns out itself to be of a type that was only introduced in late 1955, so my original guesstimate of 1952 was some way off.

Original Post Below:

With kind permission of doveson2008 at Flickr, I’m able to bring you what must be one of the first true colour images taken of Arsenal’s stadium at Highbury.

Colour photography, still or moving, came late to English football. Â Earlier innovations in photography, like the faster films of the 1890s that allowed “action” shots, or like early film photography itself, had found an outlet in football, which had itself been a fashionable craze at the time. Colour did not. When colour film reached early adopters in the mid-1930s, it did so in the south and it did so abroad. Colour photographers demanded colourful spectacle for their expensive footage to spend itself on. Neither football nor its home in the industrial north were high on the list, which is why the earliest colour footage of Leeds, for instance, shows the winners of a gardening competion in the suburbs.

Much of the early colour football photography was done by Americans, to whom the UK was all new and interesting. The first colour football film, which we think was made at Turf Moor in about 1943, was shot by a GI. This image of Highbury comes from a collection of images taken by American tourists.

It’s difficult to say much about what took our American tourist to Highbury. It’s clearly not an out-and-out football occasion. Spectators sit on terraces when you would expect them to stand. There are no goals, no corner flags, no visible lines, and the pitch itself is in pristine close-season condition. Belgian and Finnish flags flutter: there are others too hard to identify. Everyone is smartly dressed, and a good third of them appear to be women. Something orange is taking place in the paddock at the front of the East Stand.

Whatever the occasion was, they chose a perfect vantage point. Immediately to the left is the North Bank. Note how clean and fresh it looks – the new steel on the terracing rails and fencing. There’s no roof: incendiary bombs took care of that during the War, and it wouldn’t be replaced until 1956. The stand itself needed extensive rebuilding. What we have here is, in essence, a new “Edwardian-style” terrace, the last of its kind to be built at a club like Arsenal. It’s our only colour record of what such a structure would look like just out of the box.

Dominating the picture, on the far side of the pitch, is one of the most famous buildings in the game,  Herbert Chapman’s memorial, the art deco East Stand. Note the row of lamps on the edge of the roof: those are Arsenal’s first “official” floodlights, fitted in 1951 and  brand new here. Chapman had wanted floodlighting twenty years before (it was first used for football in Sheffield and Darwen in 1878) in order to help football compete with the nascent speedway for evening audiences. The Football League, its innovatory instincts knocked out of it forever by World War One, refused.

Arsenal’s first match played under the lights was against Hapoel Tel Aviv on September 19th 1951. They won 6-1: you can see the programme cover here. The season that followed would bring glorious failure. Injuries, and a fixture pile-up, saw the title lost to Manchester United in a last match decider. The FA Cup Final was lost too, more to further injuries than to Newcastle United. Arsenal finished the game with seven fit players, men who deserved more than runners-up medals for keeping the score down to 1-0.

The following year, Arsenal would win the league title – on goal average from Finney’s Preston North End – and that was, truly, the last trophy of the Chapman era. Chapman’s trainer, assistant and successor, pioneer football commentator Tom Whittaker, died three years later, and his team would win nothing for another 17 years.

What a dignified, stately place Highbury was in 1952. Good enough for people you might think; an appropriate symbol of the spectators’ worth. As fans over 40 will remember, the calming, understated green colour schemewe see here lasted until the late 1980s. Green and cream wouldn’t suit Ashburton Grove, and whilst Ashburton Grove is a raging beauty of a stadium, turning heads on trains going north out of Kings Cross, Chapman’s Highbury was unselfish with its magnificence in a way Ashburton Grove is not. Highbury, you feel, needed people. It only came to life when the fans and spectators it was built for were present and in voice. Ashburton Grove is a magnificent but inhuman sculpture, better empty, which fans clutter up in spite of themselves like litter and weeds.

In fact, the best part of Ashburton Grove isn’t to be seen from the train. From the street, the approach to the Emirates echoes the architecture of the East Stand, something that’s been skilfully done and which isn’t in the least bit mawkish or clicheed. It makes you realize just how much the East Stand is worth to North London.

How easily the East Stand might have been football’s Euston Arch, carelessly smashed and removed leaving only regrets and frustrations, futility. But that’s not Arsene Wenger’s way, or David Dein’s, and they’ve embellished their own monument by ensuring the future of Herbert Chapman’s. Chapman’s, and the nine Arsenal players who died in World War II. Chapman’s, and also Buchan’s, Bastin’s, Hapgood’s, Compton’s, Male’s and the others. Chapman’s, and how many men, women and children from North London and beyond, over 90 years.

Could this be before the first ever day/night cricket match?!

http://www.espncricinfo.com/columns/content/story/240292.html

No, ’cause no flags in picture, or no reason to have flags. Still I thought perhaps the lack of markings…

I did wonder about that game! But my instinct was that whatever occasion IS shown, has just ended, and it looks no more a cricket crowd than a football one, and then there are the national flags. My guess is that it’s some kind of get-together for national communities in the UK who originally arrived as war refugees – Belgians, Poles, Finns, Norwegians etc.