Say this for David Pearce’s novel The Damned Utd – it was the first really unembarrassed cultural treatment that the national game has ever had. Fever Pitch broke the ground. But Fever Pitch was gauche, blushing, unsure of its reception. It was essentially uncontroversial, and that is what has set The Damned Utd apart: the real hurt and confusion the novel caused, the bad memories it revived, the losses it refreshed. It may have helped cement Brian Clough in his full and proper place in the public life of the country, but The Damned Utd exhumed Don Revie and Revie’s Leeds along the way, and didn’t do the same for them at all.

Much of the drive for Richard Sutcliffe’s new biography of Don Revie comes from anger at The Damned Utd, and because the issues that the novel raised about Revie are the narrowly footballing ones, it’s these that Sutcliffe concerns himself with. Why isn’t Revie seen in the same kind of light as Busby, Shankly, or Clough? Do Leeds deserve to be remembered only for cynicism and winning at all costs? What’s the real story about Don Readies: the manager and his money? What really happened to Revie at England?

There is a wider significance to the life and work of Don Revie, which Sutcliffe leaves aside. The way Revie stands for Leeds, for instance, as the Chamberlains do for Birmingham. The sheer depth and breadth of change in the life of a man born in poverty in Middlesbrough, whose son went to Repton and Cambridge, who ended his career wealthy and honoured in the Middle East where his home is now a beloved shrine. The issue of what happened to leaders with backgrounds like Don, who before the 1973 Oil Crisis seemed set fair to rule Britain and take her into a better future.

What does it mean, too, that Don Revie was so young when he retired? He had just turned fifty when he resigned from the England job. More than half of all current Premiership managers are older, including Tony Pulis and Steve Bruce. It hardly seems possible, but Revie was largely photographed in black and white, which, unless you are a Beatle, makes you look older than you are.

All that had to be left aside. Football matches make football biographies different from those of politicians, artists and writers, because games turn careers and there are so many of them. There has to be at least one book that does the heavy digging of tracing an important career through, game by game, club by club, transfer by transfer. What we really lacked was a proper, basic, detailed reference biography of Don Revie, and this is what Sutcliffe has provided.

Revie’s Managerial Achievement

Sutcliffe wants to make the case that Revie’s achievements were equal to those of his rivals and contemporaries. Contemporaries they were, too: Shankly and Nicholson both retired in the year Revie left Leeds, Busby wasn’t long gone, and Clough was about to take himself out for three seasons.

In terms of sheer club achievement, there’s no doubt that Revie is at home with the very best. He was only at Leeds for thirteen years, and when he began, Leeds was a cricket and rugby league city. United were considered beneath not just Yorkshire Cricket Club and Leeds (Rugby League) but Hunslet and Bramley RFCs as well.

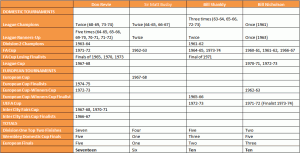

This table compares Revie’s achievements at Leeds with those of Sir Matt Busby, Bill Shankly and Bill Nicholson over the same period. I’ve included the 1975 European Cup Final because although it post-dates Revie, it was Revie’s team in Paris that night, ably shepherded by Jimmy Armfield.

(Click the chart to enlarge)

No Harry Catterick, Bertie Mee, Brian Clough, Joe Mercer and Malcolm Allison here, but the table highlights just how competitive an arena Revie found himself in. Most observers agree that the period 1956-1973 was the absolute apogee of English club football, in achievement and in absolute depth of talent. Leeds’ total of seventeen significant football achievements is some way ahead of what Manchester United, Liverpool and Tottenham managed in the same time. Yet, before Revie, Leeds had had no top-level honours of any kind. Even Clough’s clubs had won top trophies before his arrival. Revie had had to build his club from scratch.

Dirty Leeds

The manner in which Revie succeeded is this biography’s second issue, and Sutcliffe deals with it carefully. Leeds weren’t a cynical team: they were a maturing team learning their trade. Revie was protective as they grew. The “Cantona†signing was that of Bobby Collins, who really was a hard case, but he put heart and belief into the talent around him. Other teams had similar players – Chelsea have Ron Harris, for instance. European opposition spat, hacked, rabbit-punched behind the referee’s back.

In his last two years at Leeds, Revie took the shackles off his side, and they played memorable football, the kind that would have flattered Anfield or Old Trafford. But by then, the mind of the public had already been made up.

When Revie went to England, he realized that the opposition players he had worried over and warned against in his pre-match dossiers – players he now had at his disposal – were not as good as he’d thought, and that his old team, Leeds, had been much better than he had ever realised. In Sutcliffe’s account, Revie came to regret not letting his team express themselves much earlier in their development. So much more might have been won. His caution had robbed his lads of the medals they’d deserved.

Don Readies

Sutcliffe treats Revie’s financial dealings in a similar way. Revie was either innocent or no worse than his feted rivals. Revie met Alan Ball on Saddleworth Moor in 1966 to bribe him, but Matt Busby left a suitcase of cash at the young Peter Lorimer’s house in the hope of buying his signature. Sutcliffe denies outright that Revie was ever involved in match-fixing: everyone wonders why he never sued. Perhaps he didn’t want the hassle..

Match-fixing aside, Revie’s relationship with money really does have to be seen in context. Then, as now, the real control of football and the real money in football lay with the club owners. Wealthy as players are now, they are still nowhere near the level at which they could think about buying a controlling stake in a Premiership club.

Revie had come from an impoverished, insecure background. In depressed Middlesbrough, Revie’s family were worse off than most. His father found work hard to come by. His mother died. As a consequence, in adult life he took care to balance job security with income maximization. For instance, as a player, he believed in changing clubs reasonably often, and looked out for signing on fees. But as Sutcliffe makes clear, professional care accompanied great personal generosity.

Revie at England

After England had beaten Czechoslovakia at Wembley in Revie’s first competitive start, he told his son something that would prove key not only to his management but that of all of his successors. “We haven’t got the players.†In particular, he meant that there were no English equivalents of Bremner or Giles, his key Leeds lieutenants, but he was right across the board: the post-War supply of talent - nourished by fair rationing of food, playing on car-free streets, coached on proper pitches at new schools, made sensible by hardship - was fast drying up.

But Revie had issues of his own in any case. A clever man – his son, as we’ve seen, became a Cambridge graduate given the chance – he had always been a deep football thinker. Not necessarily where you’d think – the “Revie Planâ€, Sutcliffe establishes, was Manchester City colleague Johnny Williamson’s idea. But his tactical acumen and attention to detail, his novel training approaches and openness to novelty are well established. With England, however, his brain had too much time on its hands.

Revie overthought everything. In the weeks and months between internationals, his natural paranoia, superstition and caution overwhelmed his marvellous instincts for a player, a position, an on-field situation.

Nor did the techniques he used so effectively at Leeds translate to England. Sutcliffe thinks that players’ opposition to things like dossiers, carpet bowls and bingo have been exaggerated. But that didn’t mean that the Leeds family atmosphere could be rebuilt in Lancaster Gate, it didn’t mean that players could win Revie’s trust in quite the same way and it didn’t mean that the dossiers didn’t sometimes eat away at players’ confidence.

Sutcliffe makes clear that Revie was one of those who were gifted with extraordinary emotional intelligence – a man manager of the highest calibre. In the early 1960s, this had enabled him to pull Leeds together, and keep it together, by dint of the extraordinary work he put in to keep his side happy and the support staff involved. But at Leeds, he’d had everyone around him, all the time: at England, bureaucracy and the sheer lack of player contact proved more than he could compensate for.

It’s clear from Sutcliffe’s account that England were unfortunate not to qualify for the 1976 European Championship. An absurd draw against Portugal doomed England when they were by some margin the best team in a limited group. But qualification for Argentina 1978 was another thing altogether. Revie’s selection for the crucial match against Italy in Rome was so unexpected – so panicked and erratic, with players out of position and established performers excluded – that the Italians took it as a bluff at first. Then they took advantage.

It hadn’t helped that Revie’s attempts to get political with selection misfired. Sutcliffe sets out an intriguing version of events surrounding the 1975 Wembley match against World Champions West Germany. So convinced was Revie that England would be beaten handily, the story goes, that he picked the players he’d been urged by the press to pick, intending them to fail. Mavericks and playboys: Alan Hudson in particular believed that his call-up was to make sure that he’d play himself out of England contention for good.

In the event, the “new” defence of Gillard and Whitworth proved solid, Hudson ran riot, and England humiliated West Germany for ninety glorious minutes. Anyone not aware of what had prompted the selection of this particular team might consider that Revie had found a team to win a World Cup.

Revie’s disintegration was accelerated by FA machinations. Sir Harold Thompson, an enemy to Ramsey and to Brian Clough in turn, was at the heart of Revie’s troubles. It wasn’t just the secret negotiations with Bobby Robson behind Revie’s back or the comic snobbery (“Revie – when I come to know you better, I will call you Don”); it was the terrible punitive hounding of Revie once he’d left for the Middle East.

The worst one can say of Revie with regard to leaving England is that he sold the story to one paper – to Jeff Powell at the Mail, and he came to see it as a mistake in later years. But he had every right to leave, and every right to do the best for himself when he did so. If Sutcliffe’s account is true, then it isn’t Revie’s loyalty and patriotism that should be in question, but that of Thompson and his colleagues.

The story of Revie in the Middle East isn’t often told. It’s a happy one. He and his wife enjoyed their time there, and Revie was successful in kickstarting UAE football: his youngsters would take UAE from the bottom of the Arabic pile to qualification for the 1990 World Cup. He is still warmly remembered, and his house has been kept as it was when he lived there.

The rest is taken up with – taken away by – motor neurone disease.

This is the right biography for Revie, now, and it opens up the field for writers who will consider him, and what he achieved, in the life of the country as a whole. Because where does football stack up? Where do football men like Revie stand in importance to England and to the UK compared with, say, William Golding, Jennie Lee, Charles Mackintosh or Benjamin Britten? That’s for later. Richard Sutcliffe has given us both a rehabilitation for Revie and an essential reference work built around him. It’s the very least that Revie the man deserved.

“With England, however,…Revie overthought everything. In the weeks and months between internationals, his natural paranoia, superstition and caution overwhelmed his marvellous instincts…”: what does that teach about selecting an international manager? Does it cast any light on Capello?

I’ve given this a bit of thought, and – no, I’d say probably not. Three reasons:

(1) Capello is very different from Revie in personality terms and approaches his players in what is almost the diametrically opposite way. He is not prone to self-blame, or introspection and almost certainly regards the English football world as too stupid to worry too much about.

(2) Going by his own stated principles, I don’t think he’s made any major mistakes as England coach. That’s not saying I wouldn’t have done things differently – I wouldn’t have hung Green out to dry at a World Cup for a start. But England lost out to a better, smarter set of players, and really one can’t say fairer than that. Better lose cleanly than go through yet another bad-tempered exercise in extra time and penalties against Portugal.

(3) The main similarity between the two men is the choice of player available to them. The good ones are old and crocked: the new ones aren’t quite up to the same standard, and some of them are intent on frittering away their talent. England persist in doing absolutely nothing to develop new players, and increasingly turn to a combination of plastic patriotism (passion and commitment, ‘Arry for England etc) and satire (what other sport follows itself up with a James Corden show?) and whilst that continues, we’ll just have to wait for luck to deliver us another set like Beckham, Owen & co.

What does a club manager do? I suppose his footballing duties are:

1. Recommend players to sell or retire

2. Ditto to buy

3. Manage the fitness, training and practice regime for individuals

4. Ditto for the collective

5. Set tactics before each match

6. Select the starting XI and the bench.

7. Make substitutions

8. instruct changes of tactics during the game and at half time.

What have I missed?

Anyway, the international manager clearly has no duties in 1 & 2 (except perhaps for soliciting that attachment of dual-qualified players); duties under 3 probably add up to little more than seeing whether someone is fit to play; 4 presumably happens but must be largely cursory. So 5 -8 are his main duties. Again what have I missed?

Yes – that’s pretty much all of it, Dearieme. All I would add is:

1. Admin, paperwork and meetings. Revie probably had just the one person to help him with this, much of whose time would have been taken up with keeping the books. Organising team hotels, food etc., kit, equipment, stadium upkeep and cleaning…

2. Community liaison. This was part of the job from the start i.e. pre-WW1. Openings, “state visits” to local schools and firms, fundraisers – Clough had to go on large-scale fundraising on his own behalf at Hartlepools.

3. Scouting trips. In the 60s and 70s, it meant Revie, Clough & co spending days and nights on the road. If you weren’t prepared to drop everything and chase up to Scotland to snare a Lorimer or Gemmill, your rivals were.

4. Travelling to games. Leeds played an average of 2-3 games per week, a small majority of which were away from home. Revie insisted that they stay the night in hotels, so each away match took place over two days at least – more in the case of European matches.

So even when international managers like Revie were also responsible for the FA’s national training and coaching schemes (as England managers before Sven were) – it’s clear where the gaps open. And with England, you’re doing most of it with relative strangers all of whom were appointed by someone else, not your handpicked team of Leeds intimates. Patriotism aside, England has always sounded like an awful, awful job.

Under “his footballing duties” #2, I think I’d underestimated the demands of scouting. And presumably that takes up the time of an international manager too. Or, at least, gives him something to do in the yawning gaps between games.

And then at a tournament, everything changes for him.

I do wonder whether Mr Dalglish has just admitted that he thinks that Gerrard is usually rubbish for England

“And he is delighted to be teaming up with Gerrard again…”The way he has served this club and what the club means to him… Certainly he’s more influential wearing a red shirt more than any colour.””