In January, London’s School of Life held what it called “The Self Help Summit.†The Summit, culmination of years of psychotherapists’ frustration at what they call the Self Help Industry, brought together a remarkable range of (tongue very much in cheek) the usual suspects: Philippa Perry, Alain de Botton, Richard Wiseman, Mark Vernon, Frank Furedi, Robert Rowland Smith, Oliver Burkeman (who has recently published a new book, Help!). Vernon, on the School of Life’s blog here, summarized the Summit’s questions thus: “Can self help make you happy, develop your power, save your life? Or are it’s (sic) advocates peddlers of snake oil? Or again: given the genre is hugely diverse, is it possible to separate the dross from the gold?â€

I wasn’t able to attend, but if the various reports of the event are anything to go by, it went well and did better than just avoid becoming the kind of sneerathon that might have anticipated. But I want to add a thought of my own.

I’ve read a lot of self help books in my time. I met my first as a teenager. I’d fallen in love for the first time, only weeks after fastening onto my first real-world ambition. This wasn’t a situation for which my upbringing had prepared me. I knew no one in my world to whom I could ask advice from, or turn to, or trust. It was a lonely and frightening time.

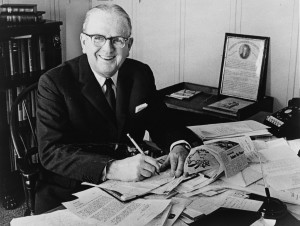

I came across a copy of Norman Vincent Peale’s Power of Positive Thinking – in WHSmiths, probably, because this was the pre-Waterstones era. Scenting that this wasn’t a book that you wanted to be seen with in public, I read it in my room – and, for the first time, ran across concepts like goal setting, perseverance, and setting your own standards. All that and more, set in an go-getting, early-century America that was far removed from the knackered, cynical world I’d been brought up in. Throw your heart over the bar and your body will follow.. Advice! Tips! Guidance! Real life examples! What to do if things go wrong! I grabbed it and hung on hard.

(The religio-social background and history to NVP and positive thinking is fascinating – start with Barbara Ehrenreich’s Smile or Die: How Positive Thinking Fooled America and the World which is, incidentally, far harder on the self help industry in toto than the Summit appears to have been).

Over the next decade, self help played a huge part in stimulating my interest in psychotherapy as a career. I quickly found myself exploring thinkers like Aaron Beck, Irvin Yalom and Anthony Storr besides. But helpful as those great names would prove in guiding my work and practice, none of them would have been any help whatsoever to my stuck and somewhat lonely 16 year old self.

I’ve found little over the years from the official mental health industry that would have been. Even the sainted David Burns, whose Feeling Good is the favourite book of Metafilter, would have proved beside the point. Later, perhaps, but not then. Self help is not always, or not even principally, opposed to or in competition with professional therapy writing or services.

Because, with so many self-help books as with certain moments in life, mental health is not the principle issue. Direction, purpose, and recovering some sense of control over life are central themes, alongside ideas of change and transformation. There are times along the way when that – something you are doing – not the emphasis on the style of your thinking found in some schools of psychotherapy – is what you really need. There’s room and a time for both – no one’s explicitly denying that, and ultimately they boil down to the same thing – but sometimes you need one so much more than the other, or you need one before it can become time for the other.

You might have noticed without my mentioning it that these are longstanding working class themes. The dream of breaking out into a different, better world: it’s the tale of every local lad done good, it’s the story behind Educating Rita and John Major’s autobiography, it’s the legend behind all those Carnegie libraries and Tesco and Amstrad and, and, and, and. Direction and purpose: they are not easy things to find, and they get harder to find, and use, with every rung down the ladder.

It is one of the classic “insults of class†– having to win for yourself the right to believe that you are entitled to form and follow your own ambitions. At the summit, Robert Kelsey attributed to self help his recognition that his sense of failure in life was in fact a fear of failure. That’s a hugely important point and he made it well. It’s also a middle class one. It’s easier to have a fear of failure when you know how and where to start, indeed, when you know you are allowed to start at all.

The need to change, to be different succeed is a familiar idea to anyone from a working class background. That, to put it bluntly, is because it’s true. It’s an easy thing for middle class journalists and writers to mock, who already have security, who already own the idea that you can achieve what you set out to do, who started life already halfway into the world most people must hustle and scramble to reach. It’s easy to mock when you’ve grown up knowing lawyers, poets, artists, bankers and academics and so assume that those fine careers are options for you. (I am lower middle class in origin and made it to 18 without having known personally any adults in any of those fields – I saw only computing, and not much of that. What about families where no one works at all?)

I’ve a friend, the child of a famous man, who has never read any self help, but knows it’s all crap. The family are wealthy: the chosen career is in a field with formidable entry costs. But I know this about my friend too: they’ve always had written goals. They’ve always used social “tricks†like mirroring and pacing in order to get on. They have a deliberate strategy to overcome failure when it occurs. They have another strategy for networking. They visualize their ideal outcomes.

So much of what they do is pure Tony Robbins. But they don’t know that, because actually, it’s just what people at their level in society do. Not overtly, or even knowingly: there’s no need. They’ll never be as self-conscious about it as people like me who have had to get it all out of a book (if not that one) because there was nowhere else for it to come from.

And I wonder if my friend, or anyone who has ever pitched an article for the hell of it, or just thought they might just – what the heck! – put in for that (interesting) job, or been called on to consult or whatever – I wonder if they have quite realized how unusual they are in British life. That their luck and fortune might lie – not in the results of their decisions, but in their assumption that they can make their decisions at all.

So I’m glad that the Self Help Summit left room for the genre to live and breathe. Without it, there’s really very little to fill the gap (the series of which this book is part is quite good) and beyond that, nothing but guides to gardening, cooking and cars, on into the distance. Even in England, that’s not going to be enough. And as for weeding out the dross – I think people might be sensible enough, resilient enough, to do that on their own.

Like your post. It may sound strange, but indeed there ARE people who don’t even know, let alone try, concepts such as goal setting, perseverance etc.

I didn’t get a chance to read the book, but my impression of Ehrenreich’s critique is that it is two-fold (and potentially reasonable):

1) Positivity (rather than self-help) can be pathological, particularly in a society (like the USA) where some religious sects are latently anti-science and anti-medicine.

2) Again, positivity can be a virtue at the individual level, but hamper the ability of a society to grapple with problems that require realism. Too much belief in individual agency is incompatible with a safety net, etc.

I think that’s right. Although she’s harder than that: positivity of this kind has rather unexpectedly dubious antecedents, and it’s doing bad things both to public culture and modes of interpersonal behaviour.

For me, the book was also significant in blowing some rather large holes in evidence-based positive psychology (Martin Seligman et al) – one of those cases where you have to thoroughly reassess something you’ve expressed strong support for in public over a long period of time. I was all for Seligman and said so. Probably not now.

I’d really like to hear more about your reassessment of “positive psychology” because up to now I’ve supported Seligman et al. (Of course I should read the book, but it’d be great if you have any thoughts…)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=76lDJlhl7pM